Articles

Understanding Decompression Theory – From First Principles to Practical Models

February 8, 2026

Introduction

Decompression theory exists because the human body did not evolve to tolerate large and rapid changes in ambient pressure. Every dive deeper than a few metres introduces inert gas into our tissues, and every ascent challenges the body to remove that gas safely.

The central problem of decompression is not absorption — absorption is easy and largely unavoidable — but controlled elimination.

John Scott Haldane – The First Framework

The first workable scientific framework for decompression was developed by John Scott Haldane in the early 20th century. At the time, caisson workers and divers were regularly injured or killed by what was poorly understood “compressed air illness.”

Haldane’s contribution was not just experimental — it was conceptual.

He demonstrated that:

- Intert gas dissolves into the budy under pressure

- Injury occurs during pressure reduciton, not exposure

- Ascents must be staged to limit stress on the body

Most importantly, Haldane proposed that the body could tolerate a limited ratio of pressure reduction without bubble formation. His early work suggested that tissues could safely handle roughly a 2:1 pressure reduction — a crude idea, but revolutionary for its time.

To model the body, he introduced the concept of tissue compartments, each behaving differently with respect to gas uptake and release. This abstraction remains central to decompression theory today.

Albert Bühlmann – Quantifying the Limits

Decades later, Albert Bühlmann expanded Haldane’s ideas into a far more rigorous and usable system.

Bühlmann’s key insight was that safe ascent limits could be expressed mathematically across a range of pressures, not just as simple ratios.

His work resulted in:

- Multiple tissue compartments with defined halftimes

- Explicit limits for allowable supersaturation

- Models valid across altitude and varying gas mixes

The Bühlmann ZHL models do not attempt to predict bubble formation directly. Instead, they define how much supersaturation is acceptable before the probability of injury becomes unacceptable.

Nearly every modern technical dive computer still traces its lineage back to this work.

Core Concepts to Understand

Tissue Saturation

At depth, inert gas from the breathing mix dissolves into tissues until the partial pressure of the gas in the tissue equals the ambient partial pressure.

This process:

- Is driven purely by pressure gradients

- Occurs continuously throughout the dive

- Affects different tissues at different rates

Saturation is not binary. Tissues exist along a continuum from completely unsaturated to fully saturated relative to ambient pressure. Importantly, saturation itself is not dangerous — injury risk arises during ascent.

Tissue Compartments

Tissue compartments are mathematical constructs, not anatomical structures. They represent groups of tissues with similar gas exchange behaviour.

Each compartment is assigned:

- A halftime

- A maximum tolerated supersaturation

- Independent gas loading calculations

Fast compartments roughly model well-perfused tissues such as blood and the central nervous system. Slow compartments approximate fat, connective tissue, and poorly perfused areas.

No diver loads all compartments equally — which is why different dive profiles produce different decompression obligations even at similar depths.

Halftimes

A halftime defines how quickly a compartment responds to pressure change.

- After one halftime - 50% of the pressure difference is absorbed or released

- After two halftimes - 75%

- After three - 87.5%

This exponential behaviour explains several practical realities:

- Short deep dives heavily stress fast tissues

- Long shallow exposures accumulate slow tissue loading

- Repetitive diving compounds slow tissue stress even when profiles look conservative

Halftimes also explain why time matters more than depth for long technical exposures.

Supersaturation

Supersaturation occurs when tissue inert gas pressure exceeds ambient pressure during ascent.

This is unavoidable. Without supersaturation, inert gas would not leave the body.

The goal of decompression is not to eliminate supersaturation, but to limit it to tolerable levels across all tissues.

Critical Supersaturation

Beyond a certain pressure gradient, dissolved gas becomes unstable and transitions into free gas — bubbles.

This threshold depends on:

- Tissue properties

- Existing bubble nuclei

- Local perfusion

- Rate of pressure change

Decompression models attempt to keep tissues below their critical supersaturation thresholds, acknowledging that the exact threshold varies between individuals and dives.

M-Values and Controlling Ratios

An M-value is the maximum inert gas pressure allowed in a tissue compartment at a given ambient pressure.

If tissue pressure equals the M-value:

- The model predicts the edge of acceptable risk

Exceeding M-values does not guarantee DCS — but statistically, risk rises sharply.

Bühlmann expressed M-values as linear functions of depth, allowing continuous ascent calculations. Modern decompression practice rarely aims to reach M-values directly, preferring to stay well below them.

Ascents, Stops, and Why They Work

Ascents reduce ambient pressure faster than tissues can off-gas.

The faster the ascent:

- The greater the supersaturation

- The higher the bubble growth rate

Stops serve to:

- Slow pressure reduction

- Allow off-gassing to catch up

- Limit bubble expansion

Safety stops primarily target fast tissues. Decompression stops manage both fast and intermediate compartments. The distribution of stops is where decompression philosophy diverges.

Bubble Formation

Bubbles form when dissolved gas exceeds stability limits and accumulates around pre-existing nuclei.

These nuclei:

- Always exist

- Vary in size and distribution

- Become activated under sufficient supersaturation

Once bubbles form, they are biologically active — not inert. They obstruct flow, irritate tissue, and trigger inflammatory cascades.

Silent Bubbles

Silent bubbles are venous gas emboli detected without symptoms.

They matter because:

- They indicate decompression stress

- High bubble loads correlate with increased DCS risk

- They reflect cumulative exposure, not just one dive

A “clean” dive is not bubble-free — it is bubble-tolerant.

The Oxygen Window

The oxygen window arises because oxygen is metabolised, reducing total dissolved gas pressure in tissues.

This creates:

- A pressure deficit

- Increased capacity for inert gas elimination

- Enhanced off-gassing during decompression

Higher oxygen fractions widen the oxygen window, which is why oxygen-rich decompression gases are so effective — especially in shallow stops.

Temperature Effects

Temperature strongly affects decompression physiology.

- Warm tissues are better perfused and off-gas efficiently

- Cold tissues trap inert gas

- Cooling during ascent can dramatically slow elimination

This is why thermal management during decompression is not comfort — it is risk control.

Hydration

Hydration affects blood volume and viscosity.

Dehydration:

- Reduces circulation efficiency

- Slows gas transport

- Increases bubble residence time

Hydration does not eliminate DCS risk, but dehydration increases vulnerability.

General Fitness

Good cardiovascular fitness improves circulation and gas transport.

However:

- Heavy exertion during ascent increases bubble formation

- Post-dive exertion can mobilise bubbles

Fitness helps — timing matters.

Practical Models to Understand

Deep Stops

Deep stops were introduced to limit early bubble growth by controlling fast tissue supersaturation early in ascent.

The logic:

- Prevent bubbles before they grow

- Keep nuclei small

- Reduce overall bubble load

However, research and field experience showed a trade-off:

- Deep stops slow ascent early

- They increase gas loading in slow tissues

- This can increase late DCS risk on long dives

Modern practice tends toward shallower-biased decompression, especially for long, helium-based exposures.

Gradient Factors (Critical Concept)

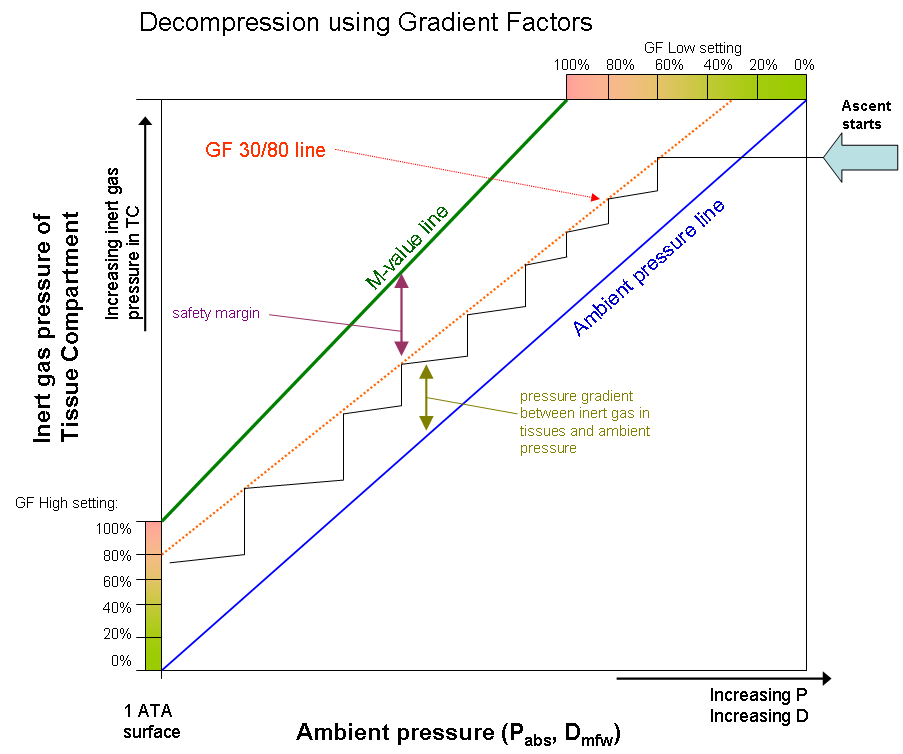

Why Gradient Factors Are Expressed as Percentages

If you’ve spent any time looking at decompression settings, you’ve probably seen Gradient Factors written as something like 30/85 or 40/70. At first glance, those numbers can feel arbitrary. Why percentages? Percent of what, exactly?

The short answer is that Gradient Factors use percentages to describe how close a diver is willing to get to the decompression model’s theoretical limits. Once you understand what those limits are, the percentages start to make intuitive sense.

The 100% reference point

Modern decompression models define a maximum amount of inert gas pressure that each tissue compartment can tolerate at a given depth. This limit is often called the M-value. Conceptually, 100% represents that maximum allowable limit—the point where the model says decompression sickness risk rapidly increases.

Traditional decompression algorithms effectively allowed divers to ride right up to that 100% line. Gradient Factors were introduced to intentionally stay below it.

So when we talk about Gradient Factors as percentages, we’re really saying:

“What fraction of the model’s maximum limit do we want to allow?”

A Gradient Factor of 80% means the diver is choosing to allow only 80% of the model’s permitted supersaturation. A Gradient Factor of 30% is far more conservative, staying much farther away from the theoretical edge.

Why there are two percentages: Low and High

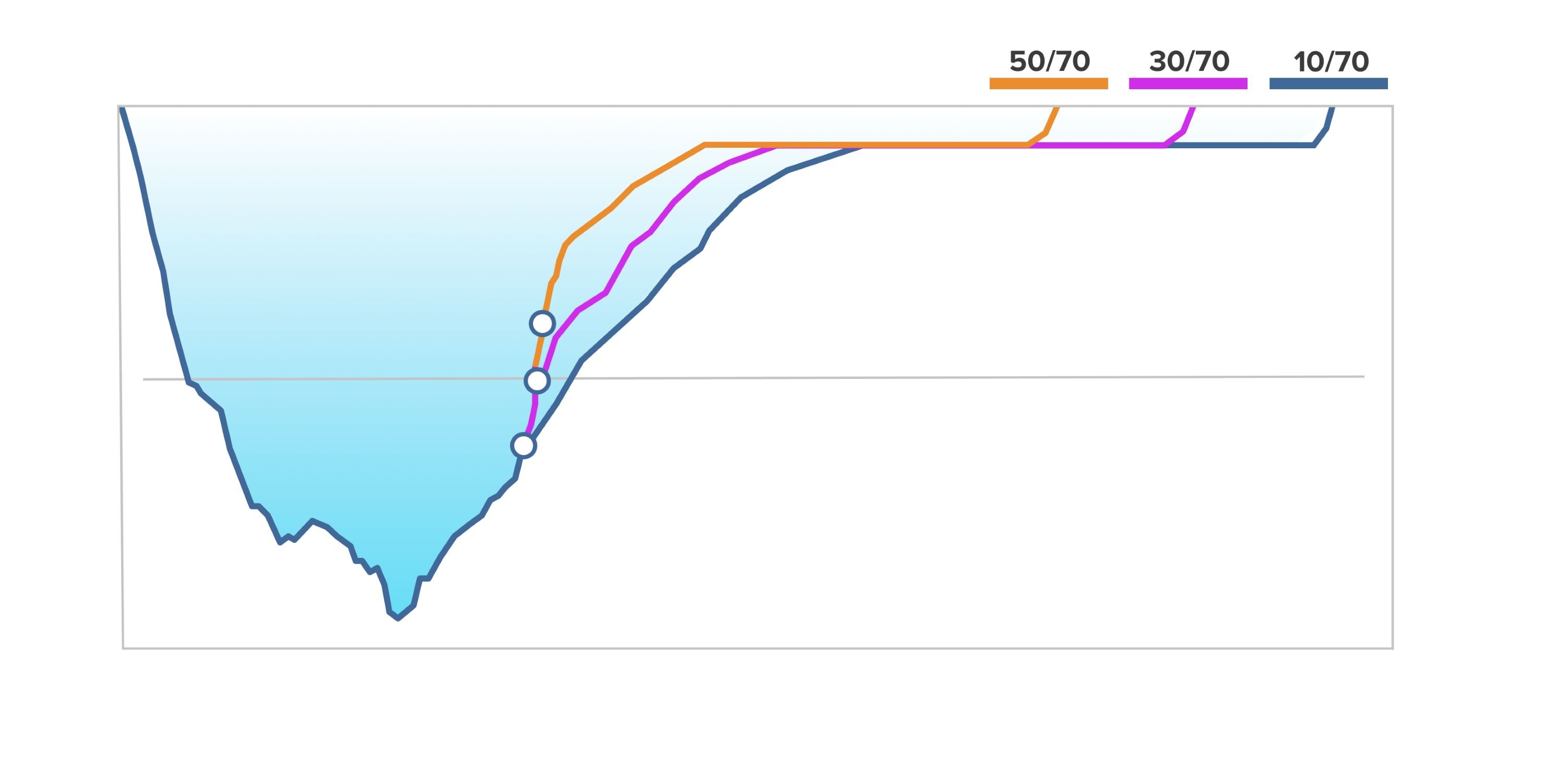

Gradient Factors are written as two numbers because decompression risk isn’t uniform throughout the ascent.

GF Low applies to the first decompression stop. It determines how much supersaturation is allowed before the ascent is slowed or stopped. A lower GF Low percentage forces an earlier, deeper first stop. For example, a GF Low of 30% means the first stop occurs when the leading tissue reaches only 30% of its allowable limit.

GF High applies at the surface. It controls how close to the model’s limit the diver is allowed to be when the dive ends. A GF High of 85% means the diver surfaces at 85% of the maximum tolerated inert gas pressure, rather than pushing all the way to 100%.

What happens between the stops?

Between the first stop and the surface, Gradient Factors don’t jump abruptly from Low to High. Instead, the allowed percentage ramps up smoothly and linearly during ascent.

This means that at every point in the decompression profile, the model calculates a current allowable limit based on where you are between GF Low and GF High. The percentages are constantly changing, even though we only write down two numbers.

Why percentages work so well

Using percentages makes Gradient Factors model-agnostic and scalable. They don’t depend on fixed depths, specific gases, or arbitrary stop rules. Instead, they adapt automatically to the tissue behavior predicted by the decompression model.

A helpful analogy is an engine redline. If 100% is the redline, Gradient Factors define how far below it you choose to operate. GF Low decides when you start backing off; GF High decides how hard you push at the end.

That’s why Gradient Factors are expressed as percentages: they are a clear, flexible way to describe conservatism relative to the model’s own limits—no matter the dive profile.

GF Low – Controlling Early Ascent

GF Low defines how close tissues are allowed to approach their M-values at the first decompression stop.

Lower GF Low:

- Deeper first stop

- Reduced fast tissue supersaturation

- More conservative early ascent

Higher GF Low:

- Shallower first stop

- Faster ascent off the bottom

- More reliance on later stops

This is not “right vs wrong” — it is risk distribution.

GF High – Controlling Surfacing Stress

GF High defines the maximum supersaturation allowed at the surface.

Lower GF High:

- Longer shallow stops

- Lower post-dive bubble formation

- Reduced neurological risk

Higher GF High:

- Shorter decompression

- Greater surfacing stress

- Higher tolerance for post-dive bubbles

GF High is often the most important single number for repetitive and multi-day diving.

Why Gradient Factors Matter

Gradient factors:

- Do not change the underlying model

- Do not guarantee safety

- Do allow intentional conservatism

They let divers tune decompression for:

- Cold water

- Long runtimes

- Team uniformity

- Individual susceptibility

They are not magic numbers — they are risk management tools.

Bubble Behaviour – Single vs Multiple Bubbles

Bubble interaction matters.

A single bubble may:

- Shrink

- Dissolve

- Be transported harmlessly

Multiple bubbles:

- Interact hydrodynamically

- Obstruct circulation

- Amplify inflammatory responses

This is why cumulative exposure matters more than any single ascent.

Varying Permeability Model and Bubble Ratio

VPM explicitly models bubble nuclei.

It assumes:

- Bubbles always exist

- Controlling early growth is critical

- Permeability limits expansion

Bubble ratio approaches extend this idea by controlling ascent pressure ratios rather than absolute limits.

These models tend to:

- Produce deeper stops

- Emphasise early control

- Reduce initial bubble growth

Bühlmann + GF vs VPM

Bühlmann with gradient factors:

- Transparent

- Adjustable

- Well-validated

- Flexible across conditions

VPM:

- Bubble-focused

- Less adaptable

- Often overly deep for long dives

Current technical diving trends increasingly favour Bühlmann with conservative gradient factors, especially for cold, long-duration dives.

Conclusion

Decompression theory is not about eliminating risk — it is about understanding and managing it intelligently.

Models do not describe reality. They approximate it.

The diver’s job is to:

- Understand the assumptions

- Recognise the limitations

- Apply conservatism where it matters

Good decompression is not rigid adherence to numbers — it is informed decision-making, built on a solid understanding of how the body responds to pressure.